“The act of shaming someone on social media is by no means new, but with the increased time people have spent on social networks over the past year, there has also been an increase in online bullying and shaming” (Ringer, 2021).

Over the years, online shaming has become more prominent with the rise of social media. “The ongoing pandemic abounds in emotionally and morally distressing scenarios… shame that is obvious on the surface tends to get much more attention than repressed, latent, or hidden shame” (Marcinko et al, 2021).

As stated by Davidoff (2002) “Current thinking suggests that shame is so devastating because it goes right to the core of a person’s identity, making them feel exposed, inferior, degraded; it leads to avoidance, to silence”.

The rise of online shaming aimed at healthcare workers in the covid-19 pandemic was significant. In addition, at the beginning of the pandemic, it was at its worst. From previous pandemics, we are aware there’s been a certain shame about being classed as ‘contaminated’ for the potential risk of spreading the disease. An example of this being the outbreak of the Ebola virus and the shame centred around healthcare workers going abroad to help with the pandemic, and accidentally bring Ebola back into their country . According to Doleful, Rose, and Cooper (2021) “Health-care workers on the front line of the COVID-19 response have been similarly shamed, sometimes leading to violence and abuse”.

The difference between previous shaming in pandemics and shaming within covid-19 pandemic is the rise of social media usage. “The internet now allows hundreds or thousands of people to participate in collective shaming, in a way that wasn’t possible before” (Meinch, 2021). Social media is a detrimental tool for online shaming as it allows people to hide behind a screen to post their opinions about someone specific.

The wearing of face masks has been known to create stigma across the world, with people’s opinions meaning they refuse to wear one. “As the Covid-19 pandemic has swept across the world, the wearing of medical face masks has become a hot topic on social media” with people being named and shamed for being seen in public not wearing one (Peng, 2020).

This topic is widely discussed since the beginning of the pandemic, with research projects arising such as Professor Luna Dolezal’s project examining how shame and stigma arose out of public health interventions in the UK. Dolezal provided an online talk at Bournemouth University.

Throughout the course of her talk, Dolezal highlighted a huge number of examples where online shaming during covid came to light, mainly for healthcare workers but also showing how shame and stigma was bought to light for ordinary people as well.

One example Dolezal explained was heartfelt about a mum who fell asleep with her son and as a result missed the clap for the NHS outside one night. The next day she woke up to being named and shamed on Facebook by someone down her street for not participating. This reinforces how Dolezal explains the pandemic shaming is community driven.

Another example of a healthcare worker being shamed was Dr Chris Higgins. Higgins returned to Australia from a trip to the US with mild symptoms however didn’t qualify for a test in Australia. He continued to see patients after he arrived home and later tested positive for COVID-19. As a result, he posted a status on Facebook explaining his situation and apologising however continued to receive online shaming and publicly naming on other social media sites (Pak, 2020).

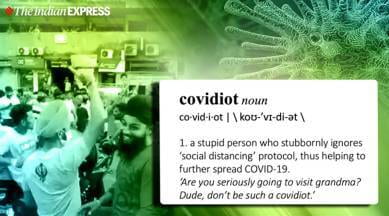

Dolezal proceeded to discuss the use of social media to create the #covidiot and war metaphors.

Touching on a more sensitive topic, Dolezal concluded by explaining the backlash and effects online shaming can have. As a result of shaming doctors and healthcare professionals, some have been bullied into treating covid-19 patients without proper PPE because its considered ‘their job’. In addition, there have been some cases across the world whereas a result they have unfortunately committed suicide.

Dolezal’s talk bought to attention the causes and effects of shaming healthcare workers during the pandemic, and the backlash they got when healthcare workers deserved respect when working during the height of the pandemic. I believe Dolezal is suggesting how social media can be used as a strong weapon against calling people out for the stigma surrounding the covid-19 pandemic.

References:

Ringer, J. (2021) COVID-19 Shaming and Social Media- a Dangerous Combination. LOMA Linda University Health. [online] Available at: https://news.llu.edu/health-wellness/covid-19-shaming-and-social-media-dangerous-combination

Dolezal, L. Rose, A. & Cooper, F. (2021) COVID-19, Online Shaming, and Health-Care Professionals. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01706-2

Meinch, T. (2021) Shame and the Rise of the Social Media Outrage Machine. [online] Available at: https://www.discovermagazine.com/the-sciences/shame-and-the-rise-of-the-social-media-outrage-machine

Marcinko, D. Bilic, V. & Eterovic, M. (2021) Shame and COVID-19 Pandemic. The Lancet, 398(10299) pg. 482-483. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/355842524_Shame_and_COVID-19_Pandemic

Pak, C. (2020) Naming and Shaming: Covid-19 and the Medical Professional. Blog Medical Humanities. [online] Available at: https://blogs.bmj.com/medical-humanities/2020/04/07/naming-and-shaming-covid-19-and-the-medical-professional/

Peng, J. (2020) “To honour cleanness and shame filth”: medical facemasks as the narrative of nationalism and modernity in China. TandofOnline. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2020.1810463

Davidoff, F. (2002) Shame: The Elephant in the Room. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.324.7338.623